Morning, CEO!

In my head, I’m still a sprite-like 25-year-old who can eat pizza at 2 AM and wake up fresh as a daisy.

In reality, my knees make a sound like a bowl of Rice Krispies when I squat, and I need a nap after reading a long email.

We spend so much time optimizing our business strategies and our tech stacks. But what about the hardware running it all?

Today, we’re looking at The Telomere Effect. It’s not a book about kale; it’s a hardware maintenance manual for the only asset you can’t trade in.

The Aglet Theory of Life

You know the Ship of Theseus? That philosophical thought experiment where you replace every plank of wood on a ship over time, and then ask if it’s still the same ship?

That’s you. You are the ship.

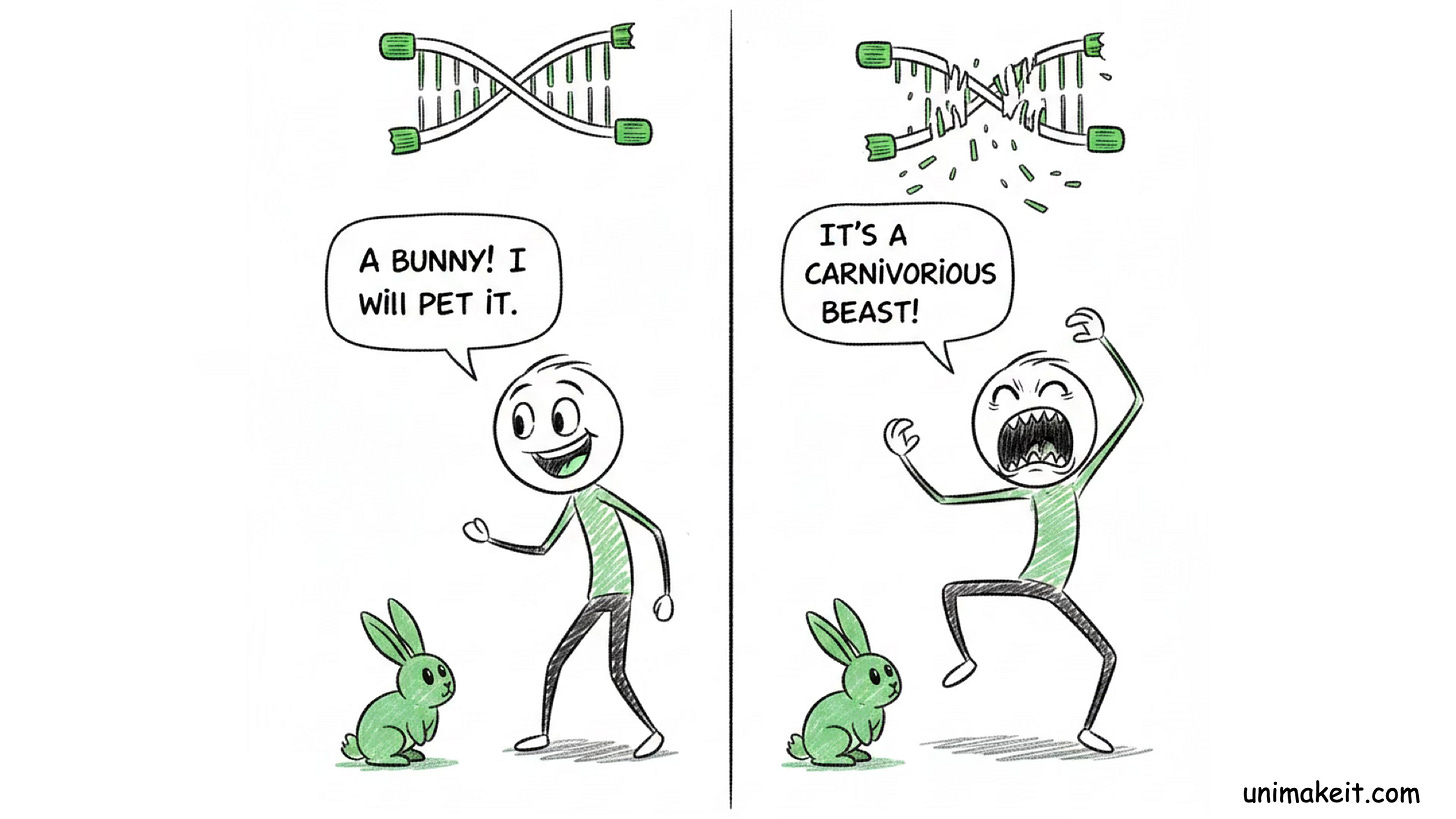

Your cells are constantly dividing and replacing themselves. You are basically a walking, talking photocopier.

But here’s the glitch. Every time your cells photocopy themselves, the copy gets slightly worse.

Why? Because of Telomeres.

Imagine your shoelaces. You know that little plastic bit at the end that keeps the lace from fraying? That’s called an aglet.

Chromosomes (your DNA packages) have aglets too. Those are telomeres.

Every time a cell divides, the aglet gets shorter. Snip. Snip. Snip.

Eventually, the plastic tip is gone. The shoelace frays. The cell stops dividing. You get “old.” Your hardware starts crashing.

For a long time, we thought this was just a clock ticking down. A genetic lottery.

But Blackburn (who won a Nobel Prize for this, by the way) found out something wild.

You can regrow the plastic tip.

There is an enzyme called “telomerase” that repairs the shoelace.

So, the game isn’t just “how much time do I have left?”

The game is: “What am I doing right now that is chewing on my shoelaces?”

Your Brain is a Drama Queen

Here is where it gets embarrassing for me.

The authors looked at mothers caring for chronically ill children. These women were under immense, objective pressure.

You’d think they would all have short telomeres (frayed shoelaces) because of the stress.

But they didn’t.

Some of them had long, healthy telomeres.

The difference wasn’t the workload. It was the narrative.

The cells listened to how the brain labeled the situation.

If the brain said, “This is a Threat. I am unsafe. I can’t handle this,” the telomeres shrank.

If the brain said, “This is a Challenge. It’s hard, but I’m built for this,” the telomeres stayed healthy.

This hits home. I am an introvert with a healthy degree of social anxiety. My brain treats a Zoom call with three people like a saber-toothed tiger attack.

The book highlights three specific mindsets that act like scissors on your DNA:

1. Hostility: That guy who cut you off in traffic? If you spend the next hour fuming about it, you are literally aging yourself to punish him.

2. Pessimism: Expecting the worst creates a biological “threat” response before the bad thing even happens. It’s paying interest on a debt you don’t even owe yet.

3. Rumination: This is my specialty. Replaying that awkward thing you said in a meeting four years ago? That’s rumination.

It’s the inability to let go.

The authors cite the “White Bear” experiment. If I tell you not to think of a white bear, you will only think of a white bear.

When we ruminate, we keep the stress response turned “ON” for hours, days, or weeks after the event.

We are burning down our own house because we didn’t like the mailman.

Your “Social Wi-Fi” Connection

In the “Agency of One” model, we glorify independence.

We are the lone wolf. The solo operator. The Batman of business.

But biologically? We are pack animals.

The research is terrifyingly clear: Social isolation murders your telomeres.

And it’s not just about being lonely. It’s about your environment.

They did a study comparing city dwellers to country dwellers. They put them in a lab and stressed them out (probably by making them do mental math while someone shouted at them).

The city dwellers’ brains lit up in the amygdala (the fear center). Their bodies were primed for danger.

Why? Because living in a dense, unconnected, or high-crime environment keeps you in a state of hyper-vigilance.

Even if you aren’t depressed, simply being “on guard” all the time wears down your shoelaces.

But here is the nuanced part that I love.

It’s not about having a million friends. It’s about “Social Cohesion.”

It’s knowing that if you fell over, someone would probably help you up rather than steal your wallet.

This applies to your professional network too.

If your clients, your peers, or your Twitter feed make you feel constantly on guard—like you have to defend your existence—you are in a “bad neighborhood.”

Toxic clients aren’t just annoying. They are aging you.

A “good neighborhood” is a network where you feel safe enough to lower your shields.

Trust is a biological necessity.

The Bottom Line

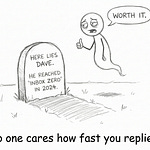

We chase productivity hacks and AI tools to be faster and smarter.

But the ultimate efficiency hack is keeping your hardware from degrading.

You don’t need a cryogenic freezer.

You need to stop chewing on your own shoelaces.

Treat stress as a puzzle, not a predator. Stop replaying the bad tapes. And find a few good humans who make you feel safe.

Now I’m going to go look at a tree and try not to think about white bears.

Links:

https://profiles.ucsf.edu/elizabeth.blackburn

https://profiles.ucsf.edu/elissa.epel

https://www.amazon.com/Telomere-Effect-Revolutionary-Approach-Healthier/dp/1780229038