Morning, CEO!

Let’s talk about decisions.

Not the easy ones. “Should I eat this donut or this piece of celery?” isn’t a decision. It’s a daily, tragic battle of wills.

And “Should I buy the high-quality, cheap thing or the low-quality, expensive thing?” is not a decision. It’s an IQ test.

We’re talking about real decisions. The ones that feel like your stomach is hosting a tiny, chaotic MMA tournament.

Which job should I take?

Should I move to a new city?

Should I start this new, terrifying project?

These are the moments where our brains, which we generally trust to run the show, reveal themselves to be... well, a little buggy.

In their book Decisive, authors Chip and Dan Heath argue that our brains are actively working against us with “Four Villains” of decision-making. But luckily, they also offer a four-step framework (WRAP) to fight back.

It’s basically a software patch for our flawed mental hardware.

Step 1: Widen Your Options

(The Villain: Narrow Framing)

The first villain is “Narrow Framing,” which is our bizarre tendency to see all decisions as a simple “yes or no” choice.

“Should I quit my job, or not?”

“Should I buy this house, or not?”

This is a mental trap. It’s like a spotlight is shining on one or two options, leaving everything else in the dark.

How to Beat This Villain:

Remember Opportunity Cost.

This is just a fancy way of asking, “What am I giving up?”

In one study, 80% of people said “yes” to buying a $15 DVD.

A second group was asked: “Buy the DVD or keep the $15 for other things?” Just reminding them “other things” existed dropped the “buy” rate to 55%.

Find the “Bright Spots.”

Someone, somewhere, has already solved your problem.

Sam Walton built Walmart by obsessively copying ideas from other stores. His “secret” strategy? “I pretty much just stole everything.”

Run Options in Parallel.

Never look at one option at a time.

A study found when designers presented one logo, clients just criticized it.

When they presented three logos at once, the client’s brain switched into a smarter, comparative mode: “Which one do I like best?”

Step 2: Reality-Test Your Assumptions

(The Villain: Confirmation Bias)

The second villain is “Confirmation Bias,” which is maybe the most insidious bug in the human operating system.

This is why, as one study found, the more media praise a CEO gets, the more they’re willing to overpay for an acquisition. Their brain is telling them, “You’re a genius! This can’t fail!”

How to Beat This Villain:

Ask Disconfirming Questions.

Actively seek out dissent. Some companies create a “Blue Team” whose only job is to find flaws in the main plan.

Check the “Base Rate.”

This is the ultimate ego-check.

Don’t ask: “What do I think will happen?”

Ask: “What usually happens when other people do this?”

Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman’s team estimated their textbook project would take 2 years.

He asked an expert, “What’s the base rate for these projects?”

The answer: “40% fail. The rest take 7-10 years.”

They all heard this. They all ignored it, thinking, “We’re special!”

It took them 8 years.

Step 3: Attain Distance Before Deciding

(The Villain: Short-Term Emotion)

The third villain is “Short-Term Emotion.” This is the internal toddler that runs our lives, throwing a fit based on whatever we’re feeling right now.

We’re anxious, so we say “no” to a great opportunity. We’re excited, so we say “yes” to a bad one. We’re hungry, so we agree to... well, almost anything.

How to Beat This Villain:

Use the 10-10-10 Rule.

Ask yourself three simple questions:

How will I feel about this in 10 minutes?

How will I feel about this in 10 months?

How will I feel about this in 10 years?

This is a magic time-travel trick that shrinks an immediate panic-monster into a tiny, logical problem.

Ask, “What Would I Tell My Best Friend?”

It’s a weird universal truth that we are all geniuses at solving other people’s problems.

This question is a simple hack to trick your brain into giving you that same clear-eyed, brilliant advice.

Anchor on Your Core Values.

A spreadsheet can’t tell you what to do.

You have to ask: What’s actually most important? Career or family? Growth or stability?

These are the real anchors. A decision that aligns with your core values is one you’re far less likely to regret.

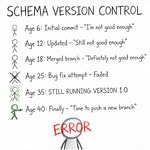

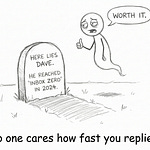

Step 4: Prepare to Be Wrong

(The Villain: Overconfidence)

The final villain is “Overconfidence.” We are all terrible at predicting the future. We are laughably, wildly overconfident in our “plans.”

This step isn’t about being cynical; it’s about being a realist. The future is uncertain, so you should build a boat that can handle a storm.

How to Beat This Villain:

“Ooch.”

Don’t just jump in. Dip a toe in. This is about running small, cheap experiments.

A company with high turnover for customer service reps had an idea.

During the interview, they started playing a recording of a real, angry customer.

This “small dose of reality” made a bunch of people quit the process.

But the ones who stayed had a 10% lower attrition rate, saving the company $1.6 million.

Run a “Premortem.”

This is a brilliantly dark and useful exercise.

Get the team in a room and say, “Okay, it’s six months from now. This project has completely, spectacularly failed. It’s a smoking crater. Let’s write down why.”

This trick frees everyone to name all the real risks they were too polite or scared to mention before.

A Story to Tie It All Together

In 1772, a pastor named Joseph Priestley (who, as a side-hustle, discovered oxygen) was broke. He had 8 kids and a 100-pound/year salary.

A rich earl offered him a job: 250 pounds/year to be his son’s tutor and his personal advisor.

The Dilemma:

Pro: The money! (A 150% raise!)

Con: He’d have to move in with the earl, losing his freedom and time for his science. What if the earl was a jerk?

Here’s how he, like a boss, used all 4 steps:

Widen Options: He didn’t just accept the “Yes or No” trap. He went back and negotiated. He created a new option: “What if I tutor your son, but I don’t move in? I’ll just be on-call.”

Reality-Test: He didn’t just trust his gut. He talked to his friends (who said “Don’t do it!”). Then he talked to the earl’s friends (who said “He’s a great guy.”).

Attain Distance (Values): He knew his core value was his research and his freedom. The money was just a tool. This clarity is what drove him to create Option 3.

Prepare to Be Wrong: He ran a “premortem.” What if this all blows up? He added one more condition: “If this partnership ends, you must promise to pay me 150 pounds a year for life.”

The earl agreed to everything.

Priestley didn’t just make a decision. He designed one. And that’s the whole point.

Links:

https://heathbrothers.com

https://www.amazon.com/Decisive-Make-Better-Choices-Life/dp/0307956393